Expert techniques and best-practise processes

Parallel narratives in 360 VR video: an experimental research project

Introduction

Since, oh, around 2008 – over fifteen years ago now – I have been thinking about how 360-degree video has the potential to challenge the fundamental ways that scripts are written and narratives are structured in film making.

A few years ago I conducted an experimental research project, with the help of Tom Mills, another immersive media specialist. The aim of the project was to test the concept of having narratives in media be conducted in parallel – multiple conversations simultaneously – rather than in ‘single file’ sequence as is normal (and indeed required) in traditional ‘flat’ media.

The challenge

360 media is different from traditional ‘flat’ media. This is a simple point and quite obvious when stated like this, but it’s still significantly underestimated. The point is that 360 media simply doesn’t have the same ‘director’s view’ as regular media. Instead of having total control over what people see, the viewer is free to look around wherever and whenever they want. This is the key thing about immersive media, but it does mean that film makers cannot rely on their audience looking in the right direction at key, narrative-defining moments in the production. The director doesn’t have the traditional ‘film frame’ to define what viewers see, and the viewer can end up with a strong sense of uncertainty.

When creating 360 video productions there are various ways that this challenging fact is tackled. The first is simply the ‘crossed fingers’ approach; the producer simply hopes the viewer will be looking at the right thing at the right time. If there’s only one area of interest in a scene then the odds of this working aren’t bad, but it’s still an approach that risks failure.

Inserting some kind of visual or audible cue to covertly influence or overtly instruct someone to look in the right direction can help improve the odds, and this is typically what’s done to try and mitigate the problem. But the reason why 360 video is created is to give the viewer a strong sense of immersion, and any too-overt ‘direction’ is likely to break this illusion of immersive reality.

Liquid Cinema has presented what I think is the most innovative approach to restoring the control film makers have enjoyed since film making began. This is called Directed Perspective (formerly called Forced Perspective), and it involves reorienting the media during cuts between scenes so that every new clip is reoriented to place the most important element in front of the viewer. This requires using Liquid Cinema’s toolkit for assembling sets of clips and defining the points of interest, and the Liquid Cinema player for delivering the results.

As Liquid Cinema’s marketing says, Directed Perspective “brings the frame back into the medium,” restoring to directors a certain amount of the control they are used to in traditional film making. This is clever and it can work very well, as long as it’s possible to deliver the final product using the custom Liquid Cinema player. However, what all these approaches have in common – from crossing fingers to Directed Perspective – is that they are just different ways of forcing the ‘director’s view’ onto a medium that, arguably, simply doesn’t really suit it that well.

The concept

Real life is parallel, not sequential; things happen simultaneously rather than in a simple sequence. We’re used to focusing and filtering to deal with this; we’ve been doing this our whole lives. We can walk into a space where multiple conversations are happening at once, and when we concentrate on one of these we ‘tune out’ the others to an extent simply by how we focus our attention.

The research project was set up to explore this specific question: is it possible to create a 360 video production that embraces the idea of truly parallel narratives rather than forcing old-school concepts on the audience?

The hypothesis is that this can make a 360 video production be more like reality. Just as in real life, where you look determines what you understand, and also what you miss, about an event or story, and what the viewer sees is all under their control. If this works, it would offer new ways to approach script writing, given that there is no longer a simple, linear narrative happening within a single framed and always-seen viewpoint.

The production

The capture part of the experiment was conducted with the help of Tom Mills, another 360 immersive media specialist; Jo Romero, a professional acting coach; and six of her students, all working actors. It was conducted in a small blacked-out theatre, and the actors were arranged in three pairs on the stage around the camera. (To reduce challenges with audio recording the action was captured in three stages, one per pair of actors, and the clips were stitched into a complete 360 sequence afterwards. With the right lavalier mics and so on it could be captured all at once.)

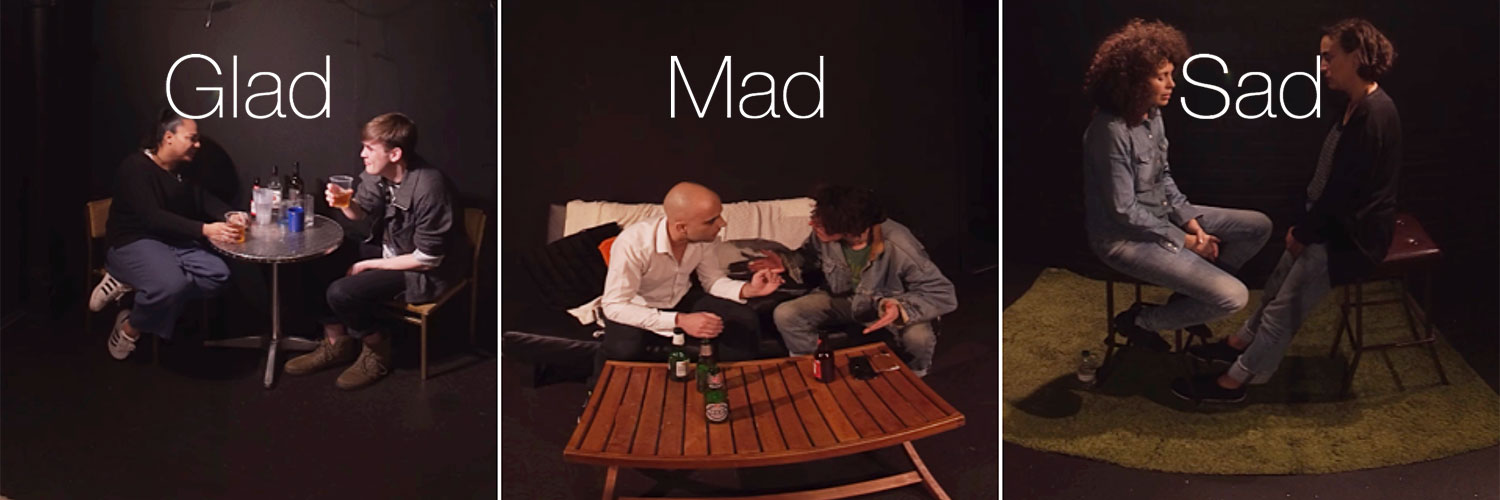

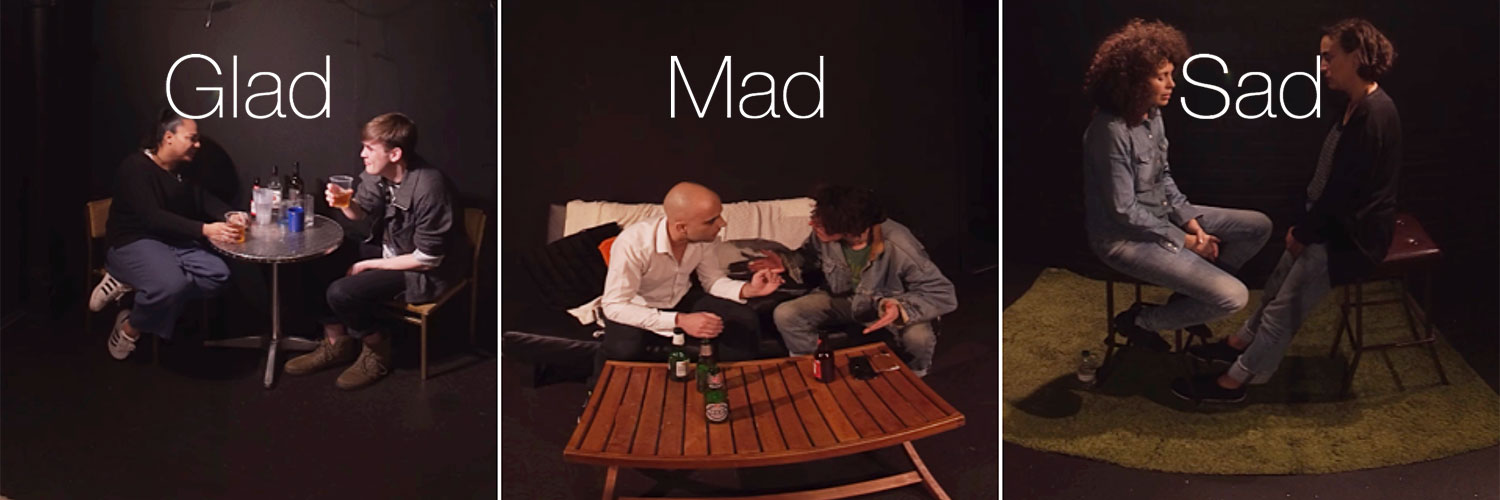

The scenario was a wake, after a funeral and some time into the event. Each pair of actors was given ‘Sad,’ ‘Mad’ or ‘Glad’ roles, and they ad-libbed from that point. The total time of the final piece was approximately three minutes.

The two actors that were given the Sad role were emotionally distraught and consoling each other. From this the viewer learns that the person who died was deeply important to this pair, perhaps a kind of role model, particularly for one of them, and they are wondering how they can go on without him.

The second pair of actors had the Mad role; they were getting progressively more and more drunk, and they were both furious. From this conversation we learn that the person who died was the partner of one of these two, and that he died through drink driving and crashing his car. Worse, we learn that he killed someone when he crashed.

The final pair of actors played the Glad role. Although they were a part of his social circle they never liked the guy who died; they thought he was an arse. They were really there for the free drinks, and they spent their time laughing a lot and reminiscing about the various terrible things the guy had done.

The current state of play

The technical challenge which has not yet been solved is how to manage the three separate audio streams that will be played simultaneously along with the video. The volume of each one needs to be ducked or raised depending on where the viewer is looking, and the sound sources need to be ‘spatialised’ so they are pinned to their location in the 360 scene. This is to simulate the real-world effect of how we naturally partially ‘tune out’ other sounds when we concentrate on one thing. The ducking shouldn’t be complete, but rather just enough to make the ‘un-focussed’ sound sources sit in the background. In this way a sudden exclamation (for example) from somewhere to one side or the other of the viewer’s area of focus might catch their attention, but it wouldn’t get in the way of the ‘focused’ sound source.

The aims

When this technical challenge has been solved and the final production has been made, its effectiveness will be evaluated in both quantitive and qualitative ways; by having people watch in headsets and observing where they look at different time points in the video, and by finding out what each person remembers and understands once they have finished watching.

What I want to determine is how much this parallel narrative process affects someone’s understanding of the overall narrative.

- Is it seen as compelling or confusing, or perhaps compelling AND confusing?

- Do people want to repeat the video and choose different views in order to expand their understanding of the story, or are they satisfied with what they learned from one viewing?

- Finally, if the narrative is unfolding simultaneously rather than sequentially, how might this affect the process of writing scripts?

Mobile: +44 (0)7909 541365, email: thatkeith@mac.com